Margaret Begbie

National Fire Service

Tadeusz Brylak

Polish Army

James Drysdale,

Gunner, Royal Artillery

Harold O’Neill, Seaman Leading Hand/Leading Steward, Royal Navy, 1941 – 1946

[Interviewed by D. Haire, in Haddington, on 24th March 2014, aged 92. Harold died on 3rd October 2017]

Harold O’Neill, March 2014.

Harold O’Neill, painted by his grand-daughter,

Fiona Mitchell.

Early Days

Harold was born in 1922 in a mining village, Annfield Plain, County Durham. He got a scholarship to the local school but experienced severe sunstroke which left him unable to perspire properly. Any exposure to sun and he suffered severely. As a result of this he found it impossible to concentrate at school and learn. By the time he was fifteen, realising he wouldn’t be likely to pass his exams, he decided to leave the village and head to London for work.

He worked for two weeks as a Strongman before being offered a job in a grocery business by a theatrical impresario, Tobias, who had expanded his concerns and had bought a chain of grocery shops. While out cutting the grass at his home, Harold heard Chamberlain announcing the outbreak of the war and was shocked when the air raid sirens went off very soon after. He found travel quite difficult at that time as the authorities shut down a lot of the Underground and huge queues formed as a result.

Harold had to go round the shop’s customers to help them fill in their Ration applications and he described how, as a handsome young man, he was often asked in for a cuppa! Harold was much influenced by writers such as Percy Westerman, who wrote tales of nautical daring-do in the inter-war years. Additionally, many of his family had served in the Forces in World War One. As a result he had a strong desire to go to sea and decided to join the Navy.

Harold Joins The Navy

Harold enlisted at Newcastle but was just handed a chit which he was told to produce should anyone accuse him of not doing his bit. In fact, Harold wasn’t told to report for duty for nearly nine months and it was only in August 1941 that he was told to report to HMS Raleigh at Tor Point in Cornwall, the Navy’s main ratings’ training shore establishment.

There he became a Class Leader and, like all the ratings, had to march everywhere. His classmates included three graduates: one from Liverpool (whom Harold later met while minesweeping the mouth of the Thames) and two from Edinburgh.

Harold was posted to HMS Drake in Devonport. While there he fire-watched during a number of German air raids but wasn’t able to go home on leave since it was too far. Instead, he tried to sleep on benches on Plymouth Ho but the town was bombed. Little sleep there that night. A friend persuaded him to join the Royal Navy Patrol Service, the arm of the navy which manned commandeered fishing and whaling ships, simply because the pay was better. Harold soon discovered that the pay might have been better but the conditions weren’t!

Harold O’Neill at HMS Raleigh August 1941.

Lowestoft

He was posted up to Lowestoft where his bed was either in local B & Bs or in a local Primary School. In the latter he had to sleep on the floor with his gas mask box as his pillow. He wasn’t posted to any particular ship but was required to report daily to an office where he’d receive his day’s orders. He was given a Canadian rifle, vintage 1903, and forty rounds and told that should the Germans invade and this ammunition be used up, he should turn and ‘…run like hell!’ His Service days in Lowestoft were aboard various ex-fishing vessels and were always wet. In addition, Harold found that it it was impossible for the crews to abide by the King’s Rules and Admiralty Instructions on board such vessels. Half the crew were civilians who’d been conscripted into the Navy for the duration but were always very relaxed about uniform or Navy procedures. Most were former fishermen. Harold spent much of the war making up his own rules and, as long as he had the O.C.’s permission, did his own thing when he was free to do so.

When he had first arrived in Lowestoft he had been told to go to the supply section and get some new uniforms. He did but was given whites, clearly intended for service in hot conditions. Harold was having none of this and told the Petty Officer that he couldn’t serve in any hot country because of his medical condition. He was sent to the Drafting Officer and repeated this story and pointed out that he’d serve anywhere, except on a hot station. ‘Anywhere: do you mean that?’, asked the officer. ‘Yes’, said Harold. ‘Would you go to Russia?’, he was asked. ‘Yes’ said Harold and that was how he ‘volunteered’ for the Russian convoys. There was, however, an additional surprise. Before he was sent to get the correct uniform, the Officer told him that he’d changed Harold’s role to that of Leading Steward! Harold knew that this simply meant there was a shortage of Stewards and that Harold wasn’t really expected to come back!

HMS Sumba

He was given six day’s leave and on his return was sent back to the Stores for the proper Arctic clothing and was transferred into Supply and Secretariat: a change of uniform as, at the stroke of an arbitrary pen, Harold, Royal Naval Seaman, was instantly transmogrified into a Royal Navy Steward! He was then drafted to HMS Sumba, a Christian Salvesen whaler (built and launched on the Tees in 1929) which had been away in the Antarctic whaling when the war had begun. When the ship made its way back north to the UK its largely Norwegian crew had been given the choice of joining the Norwegian element in the Royal Navy or staying with the ship under RN orders. Many stayed. The whaler was only a ship of some 200 tons and was given a ‘little pop gun’, as Harold called it, forrard.

Sumba was sent to escort three submarines up to Scotland via the Irish Sea but first it had to sail to Falmouth. The crew endured foul weather rounding Lands End, sufficiently bad to force the Sumba to seek shelter in Penzance. He remembers being seasick and not much caring whether the ship sank or not! The Sumba required repair and this was carried out by dockyard workers from Falmouth who came over each day till the job was done. Harold and the rest of the crew managed to get leave over Christmas while this was going on. The Sumba then sailed to Milford Haven to rendezvous with the submarines and escorted them up to Dunoon. Having successfully completed this task the Sumba carried on to Greenock.

At Greenock the Sumba was joined by HMS Sulla and HMS Svega, also ex-whalers. The issue of charts for the Arctic rather gave the game away for the crew. They realised they were indeed off to Russia. When the cat was out of the bag quite a few crew jumped ship and armed guards had to be posted to stop more following them. Two members of the Sulla thus saved themselves from a watery grave as the ship was later lost, an episode Harold describes below.

When all was ready, Sumba set sail through the Minches but ran over an uncharted rock which ruptured the fresh water tank. This necessitated a diversion to Stornaway for repair. Once the work was finished, the Sumba sailed to Iceland where, after a rough trip, the ship anchored (to the crew's relief) in the much calmer waters of Seydisfjordur. A film show ashore entertained in a stop, start fashion as the reels came to an end and were changed anew.

Convoy PQ 13 to Murmansk

The Sumba sailed out in a snowstorm to join Murmansk bound convoy PQ13, comprising nineteen ships which had set off from Loch Awe on 10th March, 1942, and now rendezvoused with Sumba off the coast of Iceland. This convoy was expected to be attacked by both U-boats, known to be in its path, and potentially by the Tirpitz, Scheer and Hipper operating from Norway. PQ13 was to have both an immediate naval protection and a distant screen of capital ships, should they be required. The weather was poor to unrelentingly foul and, after a storm on the night of 24th/25th, was badly scattered over 150 square miles of storm tossed and freezing sea. In the middle of all this lay HMS Sumba and Harold.

The scattered ships had had to move further north than desired and icing had become a serious hazard to the rather top-heavy whalers. Harold had been given the unenviable task of trying to hack ice away from the superstructure of Sumba and, in order to remain on board in the heavy seas, had had to strap himself to the funnel. He then tried to hack away the fast-forming ice, first with one hand in one direction, next with the other in like fashion. When asked how he survived the wet and intense cold, he pointed out that he was luckier than those whose duties required that they had to just stand in one place. He was kept relatively warm by his exertions. It was, however, a back-breaking job, an endless one really, since the ice reformed almost as soon as he had cleared it, thanks to so much spray and green water breaking aboard.

Harold and his shipmates were very aware of the danger of small ships icing up in heavy seas and he was surprised to notice that no one was visible doing his job on one of the other whalers, HMS Sulla, escorting the convoy. It looked like a ‘..fairy cake, a mass of ice. I could see the Sulla abreast of us and next time I looked she had gone: no sound, no sign of wreckage, nothing, and I just assumed she had turned over with the weight of ice, the ice being very thick at the time’.

Additional danger arrived when the Sumba was attacked by an aircraft. The crew manned its ‘Pop gun’ but, on firing, the barrel blew off and the explosion shattered the wheelhouse windows. The twin Lewis guns on either side of the bridge were useless as the barrels of both had been bent by the ice. Now defenceless, the crew of the Sumba were mightily relieved when the aircraft broke off the attack and disappeared. For Harold it had been a close shave as the aircraft’s bullets had come perilously close to him as they pinged and whined away in all directions.

Some idea of the horrible conditions on board can be gauged from Harold’s experience when he went into the C.O.’s cabin. There he found ice one inch thick on the bulkhead behind the Captain's bunk. The boxes holding the sweeps (for mines) had been smashed to matchwood by the waves breaking aboard and iron stanchions and iron ladders had been bent and twisted. Harold, as a young sailor, hadn't taken long to discover the awesome power of the sea. The Sumba had been equipped with ice-defrosting steam pipes at Falmouth, but these proved a dead loss, being iced up and broken.

Unfortunately for the Captain of the Sumba, the heavy seas used up too much fuel and he had to take the dangerous step of breaking radio silence to report that his ship was running out of fuel and needed assistance. HMS Fury, a destroyer, had to come to Sumba’s rescue and refuelled it under very dangerous conditions by laying out a fuel line behind. It also passed fresh bread and other provisions across. Clearly both ships were taking a big risk as both were sitting ducks should a U boat be in the area. Harold is full of gratitude for this ‘rescue’ as he is of the opinion that HMS Sumba and he would have perished had the Fury not taken the risks involved.

HMS Fury.

In Russia

The local Russian Admiral visited the ship and Harold remembers playing a game of Chinese Chequers with him which the former won. Harold got the impression that the Russians were very grateful for the assistance provided, even though the locals had been of the opinion that they wouldn’t make it to Murmansk. The local Naval commander was also impressed by Sumba’s arrival and said to Harold: ‘It’s a bloody miracle you’ve got this ship here’.

The Sumba was handed over to the Russians and the crew were moved ashore to a barracks for submarine crews. These Russian submarines were bigger than anything Harold had seen up till then. He found the cold intense and sleep difficult. The food wasn’t very attractive with lots of fat floating on the surface of the stews but Harold tucked in and fed well.

He quickly made contact with the local Russian sailors. He described being very well treated, ‘…like Royalty…’ The Russians he came into contact with were all very friendly and grateful for the efforts of the Royal Navy. He once asked sailors what they were drinking, to be told (after much use of a dictionary) ‘poison’ (i.e. home-made alcohol). Harold didn’t partake since he neither smoked nor drank.

Harold was badly in need of a wash, a shave and a haircut, none of which he’d had since Scotland. He was directed to a barber, joined the queue of fifteen or so Russians and was immediately pushed to the front! He was soon having his hair cut by a Russian female barber. He obtained a pass into the Red Fleet Club and was later given a pot of Cherry jam by a sailor friend for whom this would have been a significant gift in such a place of austerity. There was little for sale in the shops but Harold bought some face powder for his fiancé who later reported that it was a bit like brick dust and unusable.

He was taken further up the Kola inlet and was present in Rosta when HMS Trinidad docked and unloaded its dead and wounded. Trinidad had been the victim of one of its own torpedoes which had gone in a circle thanks to a frozen gyro and had hit below the bridge with over thirty casualties. He found this a difficult experience. Many of the Marines who’d been above the point of the torpedo’s impact were, Harold felt, suffering from Shell Shock.

The port area was divided up into sections with high wire fences and guard houses all round. Harold and the crew had to go through two of these check points to visit the cinema and had to show their passes at each. He quickly discovered that it was quite usual to be asked for his ID at the point of a bayonet! He made friends with two Russian submariners, both of whom had attended Leningrad Naval Academy and could speak a little English. Harold’s few words of Russian and sign language sufficed for communication.

Harold talked of how he and his mates had many preconceived ideas about Communism but found that actual Party members were very thin on the ground. This didn’t prevent frequent deafening propaganda broadcasts from omnipresent loudspeakers and there were plenty of propaganda posters displaying German atrocities. Harold found it interesting that the reality of Communist equality didn’t stretch to the seating arrangements in the cinema: Lieutenant Commanders and ORs down below and superior officers upstairs in the balcony.

A Norwegian pal suggested they go skiing, something Harold had never done. He obtained skis from the Russians and tried his luck. Unfortunately for him, he didn’t know how to stop and badly injured both his knees. He was impressed by the Russian efforts at protecting their supplies. They had constructed large caves in nearby mountainsides and light railways ran supplies in to these storerooms cum air raid shelters.

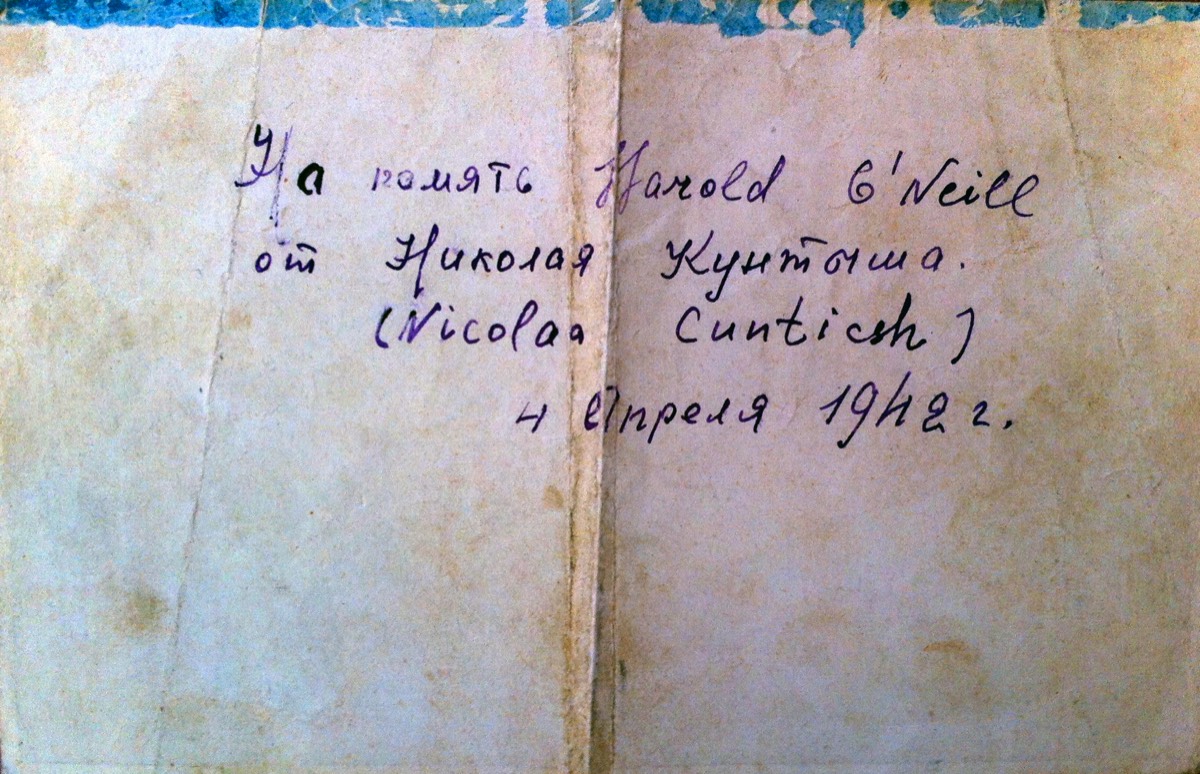

A Russian postcard given to Harold by a Russian sailor in 1942.

Convoy QP 10 Home

Finally Harold was told to report to HMS Liverpool, a light Cruiser, since Sumba had been handed over to the Russians. He was to travel home to Scapa with his officers but was greeted with the command to ‘Get lost!’ He was told to take his meals in the wardroom galley, told where to sleep and was otherwise told to stay out of the way. Apparently, the Royal Navy regarded him and his pals as little better than pirates. The only job he was given was to check the security of cleats around the ship. This was done by giving them a good thump with a wooden mallet.

Harold returned home in Convoy QP 10 escorted by seven destroyers (two of them Russian), four minesweepers and two trawlers. HMS Liverpool provided close cover and the convoy was heavily attacked by aircraft and submarines during the first three days of sailing. Three ships were lost but the Germans lost too, six aircraft downed and one damaged. On reaching latitude 30º east the two Russian ships and three British minesweepers returned to the Kola Inlet.

HMS Trinidad.

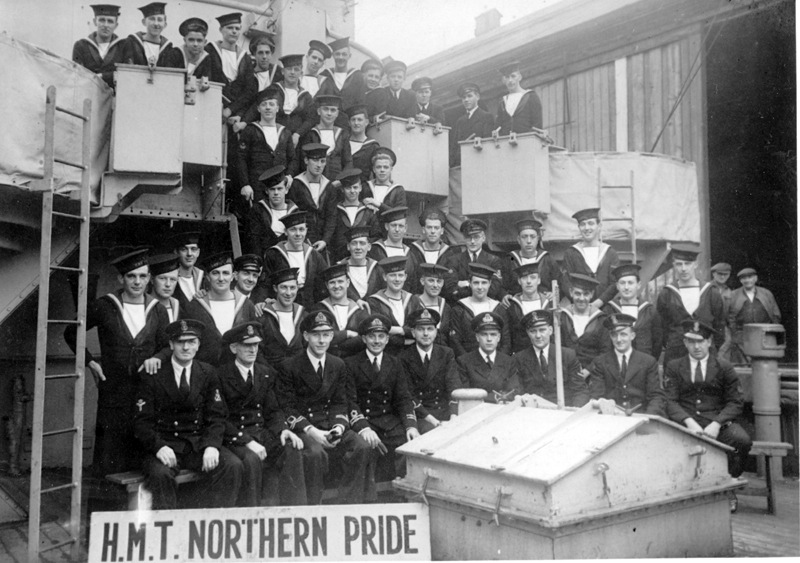

HMS Northern Pride

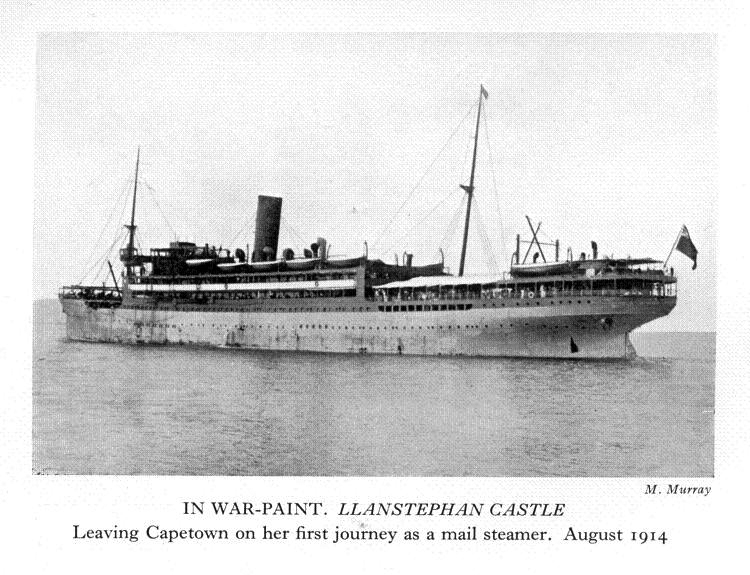

Harold resumed his travels and was sent by troopship (Llanstephan Castle) to Reykjavik where, in the middle of 1942, he joined HMS Northern Pride, an anti-submarine warfare trawler of 655 tons. Northern Pride had, ironically, been built in Bremerhaven after World War One as part of the Reparations payment. Life was pretty basic and uncomfortable aboard. He had no washing facilities at all. Extra men were required to man the armaments the Northern Pride carried and all slept in the old hold, formerly used for storing the fish. It was always cold and damp or just plain wet. The food wasn’t great either since there were no fridges and meat was kept in brine. Harold didn’t like the look of the meat once it was hauled out of the barrel. It reminded him of unmentionable innards.

Harold’s next spell of active service was spent on Northern Pride escorting convoys across the Atlantic and he noted that there was ‘…a lot of U-boat activity’. His ship was equipped with RDF and Asdic and the Captain had instructions not to stop to pick anyone in the sea up. It was simply too dangerous for a ship to stop, even for such a basic humanitarian task.

Northern Pride with a tanker ablaze behind: painted by Harold.

Once he’d recovered he rejoined Northern Pride and headed back to the UK. The boat was not a nice one to sail in as it pitched, rolled and then corkscrewed, thanks to the extra weight of armaments up top. All the crew, regulars and all, were sick. As the weather wasn’t good Harold (who frequently volunteered for duties ‘…just for the sake of variety’) volunteered to help the stokers who were exhausted feeding the boilers in such heavy seas. The boilers had to be kept at full stretch to enable the Northern Pride to keep its bow to the wind and waves, otherwise it would have been in danger of turning turtle. His job was to trim the coal in the chutes so that the stokers didn’t have to keep doing this extra but necessary job. (trimming the coal meant moving it down the chutes from the bunker to the point where the stokers could reach it with their shovels).

Run down by his recent spell in hospital and all this heavy work, Harold was experiencing severe pains in his ears by the time they reached Greenock and he was sent to the shore establishment, HMCS Niobie, just above Greenock. There he had a cyst drained and was discharged on Christmas Eve. He didn’t join the others immediately, knowing that they’d be heavily into the celebrations so he rejoined them the day after to find the Christmas dinner burnt and uneaten in the ovens and the crew flattened by the drink.

[A number of copyrighted photographs of HMS Northern Pride exist on the web - type in ‘HMS Northern Pride’]

The Northern Pride crew photographed by a Belfast dock in 1942.

Harold may be the figure fourth from the top right wearing a tie.

HMT Strathgarry – Gunnery Practice

Harold was next sent to serve aboard HMT Strathgarry, a Scottish trawler fitted with guns to allow trainee gunners to practice from aboard ship and which was based at Lowestoft. Since this port was only accessible at close to or at high tide, the Strathgarry used to set sail as and when possible and then lie off the coast to await the arrival of the trainees by motor launch. Strathgarry was a very old lady with gas lighting and a coal fired boiler. On one occasion she was attacked by aircraft coming in low beneath the radar. Unfortunately one sailor was killed in the galley and another had a bullet through his leg as he emerged from below. The ship’s gunner fired the Oerlikon but a shell in the magazine exploded and badly injured him in the groin. Harold, as the ship’s medical first-aider (untrained, as he likes to point out!) attended to his wounds and got him wrapped up in a special stretcher which was hoisted by derrick off the ship once they docked. Harold then got a row from a doctor for not having given him morphine but Harold had asked the wounded man if he could feel his legs and the man had been much more worried about losing his berth on the ship then he was about any pain. ‘I can’t feel anything: my legs are numb’, he said. Harold didn’t see the need for morphine so close to trained medical support on shore.

Harold went back to sea at the start of 1943 when he was sent to Belfast via Stranraer. He was taken to a relic of the Battle of Jutland, HMS Caroline, a preserved light cruiser which was being used as accommodation in the dockyard area. The Caroline is still berthed there today and remains the second oldest Royal Navy vessel still afloat, after HMS Victory. Harold described an amusing story about his arrival there with a group of ratings, plus one: the unknown addition asking if this was Inverurie? This misplaced Stoker was to spend the rest of the war in Belfast sailing up and down the Lough doing this and that free from much danger. A lucky slip for him.

HMS River Leven

Harold ‘misplaced’ an order to return to Lowestoft but had to move sharpish when it was repeated as a matter of ‘High Priority’ the next day. He was posted to Southampton as part of the invasion force. The area was crammed with Yanks and Harold joined HMS Loch Leven, a fishing trawler equipped with a machine for making smoke to cover the landings. Harold had great difficulty finding the Loch Leven as the Port Authorities, to whom he had reported for duty, had no idea the ship existed, let alone where it was. Harold went back and forth to the office for a week without result but eventually it did return from its work at the Landings and he was able to join it. On board he found the food was terrible, so bad in fact that he persuaded the officers to allow himself and a Buckingham Palace trained Steward to cook for them. The quality of the food improved for everyone. The Leven was sent to North Shields so Harold had missed his chance to take part in the Normandy Landings. As they sailed out of the Thames estuary hundreds of aircraft droned overhead. Later he learnt he had witnessed the gliders and Dakotas heading for the Arnhem drop in September 1944.

MMS 265 - Minesweeping

Once back in Lowestoft Harold joined MMS 265, a wooden hulled ship employed in minesweeping. The ship was used first to clear the Thames Estuary of mines and then to clear paths across to Ostend and back to Dover. Harold said that there were ship’s masts sticking up everywhere inshore around the port since the water was relatively shallow and there had been heavy losses due to mines, etc. Harold’s next period of service came about because General Montgomery required the use of a large port to help supply the Eighth Army in its drive up the coast through Belgium and into Holland. The chosen port was Antwerp but this lies quite far inland and the approach had been very heavily mined and booby-trapped by the Germans. Additionally the German army still controlled access to Antwerp from the island of Walcheren which lies on the north side of the Scheldt.

The MMS 265 tied up at a small port where the pre-war river pilots had operated from. He found one ashore searching in the rubbish bins for food, so Harold took him aboard and fed him. There was a very severe food shortage in Holland at this time. The operation of clearing the mines was very difficult. Many different types of mine had been sown, some dummies, many real, some magnetic, some not. Some had been placed in close to wrecks so that the normal sweeps couldn’t reach them and they had to be neutralised by hand, a dangerous job carried out in a great rush so as to be completed before the tide came in again. The job was complicated further by the difficulty the river pilots had in finding their way. After all, the river had had over five years to redesign its sandbanks and all the pre-war knowledge was of little use by now.

MMS 265 painted by Harold.

Victory Celebrations In London

Harold’s war came to an end when he was in Queenborough, a small port on the Isle of Sheppey in the Thames. He was told he could go up to London to take part in the Victory celebrations as long as he was back for 3am for sailing. Since his wife was nearby both were able to go. They travelled up to Piccadilly where an American band was playing but his small wife found the crush too much and they moved on to the Victoria Monument outside Buckingham Palace where another huge crowd had gathered in the hopes of seeing the King. Every nationality under the sun was represented in that crowd and all were, in the end, able to see King George, Queen Elizabeth and Prime Minister Winston Churchill appear on a balcony to wave to the excited crowd.

As Harold said, “I had been bombed, shelled and machine-gunned but I’d lived a charmed life. When it all ended there was a huge sense of relief.” After the war Harold spent a number of months helping to clear the sea lanes of mines from Dover along to and up the Dutch coast. He worked to clear access to and from Antwerp, Rotterdam and along the IJmuiden to Amsterdam.

When Harold arrived in Ijmuiden he had to report sick, having coughed up blood probably as a result of a burst blood vessel. He was put on ‘light duties’. These consisted of taking charge of a working party of Wehrmacht soldiers to help clean the heads on the ship. A bi-lingual soldier was his interpreter and he can probably claim to be the only Naval Steward ever to have had charge of a party of German soldiers!

Into The Reserves

After he had left the Royal Navy, Harold joined the Tyne Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and took part in the 25th Anniversary on Horse Guards Parade in front of the ‘new’ Queen Elizabeth. He served on a frigate in Norway and in HMS Perseus (an aircraft carrier) in Bermuda and the US. While in the latter he saw the battleship Missouri come into harbour. This had been the ship upon which the Japanese surrender had been signed.

Minesweeping The Scheldt

What follows is Harold’s own account of the

‘Clearance of the River Scheldt: 2.11.1944 – 23.12.1944'

“This great river, winding up from the North Sea leads to the port of Antwerp. Both the Allies and the Germans knew that once the port was captured by the [Allies] it would become vital to the supply of the advancing troops and armour as they liberated Holland and invaded Germany. Inevitably, a great effort was made by the Germans to render the river unusable and an equally great effort by the British to sweep it.

At one time up to 112 minesweepers were working on the main river clearance, in addition to the fifty sweepers working outside on the approach channels. After the great assault on Normandy this clearance must rank as one of the greatest minesweeping operations of the war, even on the same level as the major US operations in the Pacific, including the assault on Okinawa. The Westerschelde, as the estuary of the river is called, is sixty kilometres long. At its mouth between Flushing and Zeebrugge, it is up to five kilometres wide, but it narrows considerably on the way up. The channel is winding with numerous sandbanks, the tidal range is considerable and poor visibility, especially in the winter months, is quite frequent. Altogether a set piece for a major minesweeping problem, with large numbers of sweepers trying to operate with long tails in confined waters.

The plan was that, of the two major British minesweeping forces in the Thames estuary, that from Harwich, called Force ‘B,’ would be responsible for the sweeping of the outer approach channels to the river, while the Sheerness force, called Force ‘A’, would provide the sweepers for the river clearance. In the meantime, of course, all the Thames and East Coast working channels had to be kept swept as well.

An essential preliminary was the assault on the Island of Walcheren on the north side of the river entrance, near the port of Flushing. The landing was bitterly contested; but the sweepers swept in the bombarding battleship Warspite without loss. As the great ship passed inshore through the dawn mist past the tired sweepers, her signal lamp blinked: ‘Your difficult task is done: my easy one is now beginning’.

On the 3rd November 1944, Zeebrugge, on the southern shore, was captured. Force ‘A’ had left Sheerness on the 2nd but, on arrival, was turned back by shellfire from Knocke. Three MMSs were damaged by shells but the battery was captured on the following day and the sweepers could proceed.

Force ‘A’ now swept through the ships of Force ‘B’, which had completed their initial search of the approach channels, and swept on up the river to Temeuzen, twelve kilometres upstream, which they were to establish as their base. They were to have been met by LCPLs [Landing Craft Personnel (Large)] from Ostend, with snag line sweeps, but the weather was too rough for them. Fifty mines were swept in the day and, while this was happening, port parties arrived on the quays in Antwerp to clear them ready for handling merchant ships.

Over the following two weeks sweeping was carried out under full pressure. In the outer approaches the greatest problem turned out to be moored mines with heavy chain obstructors, which the MMS [Motor Minesweeper] could not lift. The Eighteenth Flotilla of fleet sweepers was sent in to drag these mines out of the channel. There were great numbers of ground mines in the river and they were detonating at quite a rate during these two weeks. The total bag in the river itself was 237, made up of 167 magnetic, 34 acoustic and 36 moored. Up at Antwerp the port parties used portable magnetic pulsers and searched the lock entrances and narrow passages. They cleared fifty-one ground mines as well as searching four million square yards of quay.

However, it was not a simple clearance operation. The E-boats, based only one hour’s run by night up the coast to the Hook of Holland, re-mined the approach channels as fast as they were swept and aircraft laid many more mines in the river by night. One hundred mine watching posts, manned by 600 Dutch civilians, were put into operation on the riverbanks during the month.

The sweepers persisted. Dan-buoys [marker buoys] laid at one mile intervals marked their triumphant progress, and double-flagged Dans marked the position where permanent buoys were to be laid. Their persistence was rewarded. On 26th November the first three coasters arrived safely at Antwerp, but with everyone holding their breath. On the 28th, the river was declared free of mines and that same day nineteen merchant ships arrived in port. The great supply operation over the beaches in the Bay of the Seine had finally served its purpose. Now the sweepers had opened the way to a much shorter supply route.

Force ‘B’, which had swept twenty-four ground and one moored mine in the approach channels, returned to Harwich on 28th November but Force ‘A’ stayed on the river until 23rd December before returning to Sheerness, sinking a midget submarine on the way for good measure. They lost only two ships in this great operation – ML 916 on a ground mine in the river and MMS 257 on a moored mine in the outer channels.

One fascinating experiment was tried, when magnetic ‘Oysters’ were suspected in the river. Two BYMSS [British Yard class Motor Minesweeper], 2189 and 2188, anchored nine cables apart and streamed their LL Tails. Then, with no movement to activate the ‘Oyster’, they pulsed their magnetic mines without weighing anchor. They swung on the ebb and the flood without interfering with each other’s tails and swept a different patch each time. BYMS were used, as they were not dependent on batteries for LL sweeping, and the path swept was reckoned as 300 yards long, 600 yards wide and magnetically swept to seven milligauss. The weather was atrocious, they needed to take shelter on several days, and it took seventeen days to complete this sweep.

It was, in fact, one of the most difficult and dangerous operations of the war and it was only due to the high efficiency and unremitting energy and zeal of the minesweepers working under the inspiring leadership of Captain H.G. Hopper RN that the clearance was effected in twenty-two working days, six days inside the estimate. Seventy-five mine lengths of channel had been swept seventeen times and 267 mines had been detonated.

River Scheldt mine clearance force.

Force ‘A’ River clearance from Sheerness. Captain Hopper

1 Headquarters ship (HMS St Tudo) RN No1C with ML as tender.

7 Trawlers - for stores, fuelling and survey.

1 MFV for LL sweep maintenance.

3 flotillas of BYMS – thirty ships.

5 flotillas of MMS – thirty-six ships including four Dutch.

2 flotillas of MLs – sixteen ships.

1 flotilla of LCPLs of six ship fitted with snag line sweep.

4 flotillas of MFVs – twenty-four ships for river work.

Total – 112 ships

Force ‘B’ Estuary clearance from Harwich.

Fleet and MMS as necessary.

Total – fifty ships

Total MS force at peak – 162 ships.

Harold ‘liberated’ these photographs of Germans who had been servicing and supplying E Boats operating out of Ijmuiden during the war.

Copyright: Harold O’Neill.

Copyright: Harold O’Neill.